From Algorithmic Music to ChatGPT

When we think of "artificial intelligence" and "content generation," we often focus on text, images, or conversational responses. But the roots of this phenomenon are deeper and older than they might seem. And, interestingly, an important part of this story begins with music.

🎶 The origin: music written by machines

Algorithmic music is not a 21st-century invention. Back in the 20th century, composers like Lejaren Hiller and Iannis Xenakis explored musical creation through mathematical rules and algorithms. This approach wasn't just about generating random melodies, but about exploring new expressive paths where calculation replaced intuition.

Unlike improvised music, algorithmic music aimed to detach from the creative self and give way to pure abstraction: what would a symphony created by a rule sound like? The challenge was (and still is) to find meaning in something generated by a process that, in theory, has no emotions or intentions.

🐒 The infinite monkey metaphor

The infinite monkey theorem states that if a monkey randomly presses the keys of a typewriter for an infinite amount of time, it will eventually produce any conceivable text—including the complete works of Shakespeare.

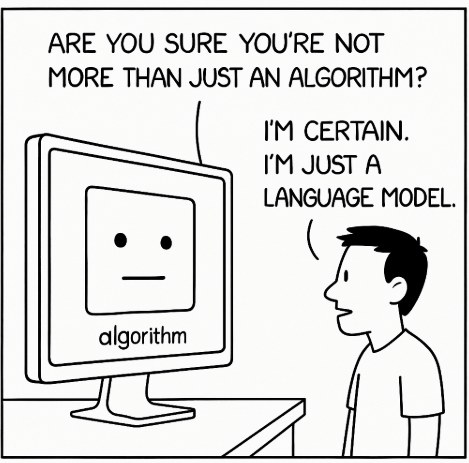

This idea, as absurd as it is unsettling, is key to understanding the heart of many current algorithmic generation technologies: it's not about understanding, it's about statistics. When a system generates a sentence, it doesn’t “know” what it's saying. It simply calculates which word is most likely to come next.

🤖 From randomness to language

Language models like ChatGPT don’t work exactly like a monkey hitting keys, but the underlying logic is similar: to produce coherent text based on statistical patterns extracted from a massive training corpus. The result may seem magical, but it’s pure computation.

Now, if systems generate more and more content online... what happens to quality? If the internet fills with AI-written texts trained on other AI-generated texts, could we end up in a loop where originality vanishes and repetition reigns?

🧠 Between automatism and the unconscious

The idea of writing without consciousness is not new. In the 20th century, the Surrealists practiced automatic writing as a way to access the creative unconscious without rational filters. André Breton, Artaud, and Dalí wrote by letting thoughts flow, without censorship or predefined structure.

It’s not so different from how some generative systems work: they repeat patterns, produce unexpected outputs, and sometimes create works with a strange kind of charm.

📚 And what does Horace Walpole have to do with all this?

In the late 18th century, English writer Horace Walpole published Hieroglyphic Tales, a collection of satirical stories full of absurdities, wordplay, and semi-narrative nonsense. Some critics have seen in this work a kind of "proto-text generator": a literary attempt to explore the chaos of language and meaning when rules aren’t clear.

This approach—playful yet critical—makes us think: to what extent can algorithms be creative? And we, as readers, how do we identify what has value amid so much statistical repetition?

❓What now?

We are facing a silent revolution. Millions of texts, songs, and images are being generated by systems that don’t think but mimic thought. This forces us to rethink creativity, ownership, and even the meaning of culture itself.

- Can we consider a melody generated by an algorithm as art?

- Does it make sense to write a poem if you can generate a thousand?

- How do we distinguish noise from the human voice?

And perhaps the most unsettling question: if reading no longer means listening to a person, but to a system... who are we really listening to?

✍️ This article may have been generated by an algorithm. It’s unclear whether what it says is true, but it definitely sounds coherent.